[01. Responsible

Packaging is responsible when it becomes everyone’s duty towards everyone else: in its design, production, and use. Responsible packaging carries quality and combines environmental protection with respect for the needs of all users.

Smart Packaging for Sustainability: Rethinking Packaging between Technological Innovation and Ethical Responsibility

In today’s world, marked by profound social transformations, environmental crises, and increasingly rapid technological innovation, packaging too is called upon to evolve. At the heart of the debate – and of new European directives such as PPWR – lies the urgent need to rethink packaging in a sustainable, transparent, and responsible way. In this context, “Smart Packaging” can serve as a strategic lever to combine technology, responsibility, and systemic evolution.

We are living in a time when the urgency of change permeates design choices, production sectors, and everyday actions. In this scenario, packaging—still often dismissed as a symbol of waste or pollution—can no longer be seen as a mere accessory to be quickly discarded. On the contrary, it represents a crucial node in the goods system, both from a production and a cultural perspective.

Every package reflects a system of values—whether explicit or implicit—and holds a transformative potential that should not be overlooked. Designing packaging today means considering not only the technical requirements for protecting and containing the product or the brand’s communication needs, but also ethical considerations: from the sustainability of materials to the inclusiveness of the user experience, from the transparency of information to the circularity of processes. Rethinking packaging therefore means questioning not only its materiality, shapes, and practical functions, but above all the kinds of relationships it can foster—through technology—between individuals, organizations, society, and the environment.

This is the direction in which so-called “Smart Packaging” is heading: an evolution that is not only technological, but also socio-cultural, urging us to design with greater awareness and a systemic perspective. But what does “smart” truly mean in this context? And what contribution can it make to a more sustainable and ethical future?

Accordind to ISO Standard 6608-1:2024, the term “Smart Packaging” refers to a wide range of solutions that integrate technology to provide advanced functionalities, going beyond simple product containment and the traditional uses of packaging.

Three main types have been identified. “Active Packaging” refers to packaging that can interact with the internal environment of the package to extend the product’s shelf life, enhancing its quality and safety—for example, by absorbing moisture or releasing antimicrobial agents. “Intelligent Packaging” integrates sensors and indicators capable of monitoring environmental parameters—such as temperature, humidity, gas presence, or impact—and providing real-time information about the condition of the contents, such as a break in the cold chain or a fall during transport. Finally, “Connected Packaging” uses QR codes, RFID tags, NFC, or other data carriers to activate digital content, certifications, traceability systems, and forms of user interaction. It links the packaging to digital platforms, enabling a dialogue between the physical and virtual throughout the product’s entire life cycle.

Beyond these three categories, there are also hybrid solutions that combine advanced connectivity, sensing technologies, and predictive algorithms, aiming to manage complex data across the supply chain and support new models of production, consumption, and service.

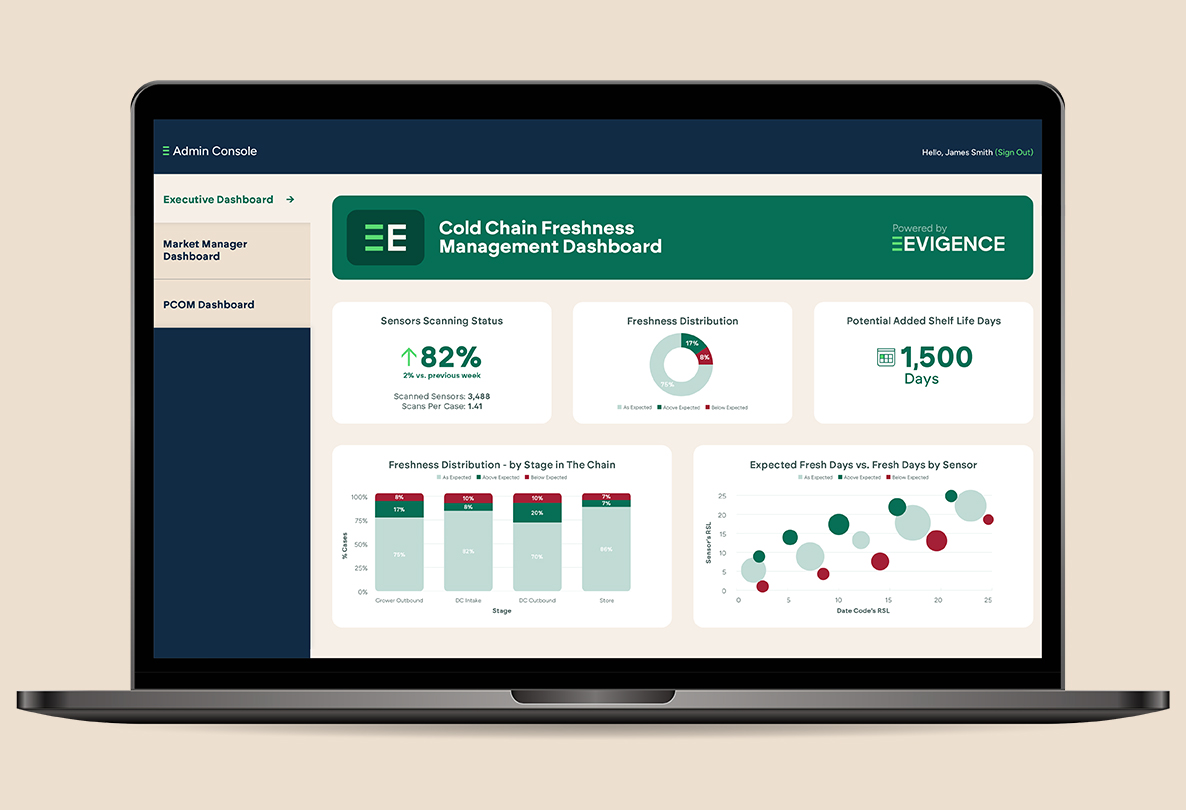

Thanks to digital technologies, packaging is evolving into an intelligent and interactive device, capable of dynamically monitoring, informing, and connecting the product, the consumer, and the entire ecosystem. An example is FreshSense di Evigence, which uses sensors and data analysis to monitor food freshness in real time, optimizing supply chain management and reducing waste.

The integration of smart technologies into packaging can significantly contribute to sustainability—but only when accompanied by a critical and responsible approach.

It must be clarified, however, that sustainability does not concern only the environmental dimension. In the 1990s, John Elkington coined the term “Triple Bottom Line” (TBL), a model that assesses business performance not only in economic terms but also in relation to social and environmental impact. This approach, also known as the “three Ps” – Profit, People, Planet – offers an integrated vision of sustainability, combining environmental protection and social equity with economic growth.

A business is truly sustainable only if it can generate shared value across three interdependent dimensions: economic strength and the ability to create long-term value (Profit), social equity and community well-being (People), and respect for and regeneration of the natural environment (Planet).

Building on this model, the United Nations 2030 Agenda further expanded this perspective by introducing an even more comprehensive vision based on the “five Ps”: in addition to People, Planet, and Prosperity (in continuity with the original 3 Ps), it adds Peace—understood as the promotion of just, inclusive, and peaceful societies free from fear and violence—and Partnership, meaning cooperation among governments, businesses, civil society, and citizens to jointly achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Among its environmental benefits, Smart Packaging can, for example, help reduce food waste by monitoring product freshness and improving preservation; optimize transportation and logistics through the collection and processing of large volumes of data and real-time tracking; and promote proper waste management by providing consumers with digital instructions—such as interactive QR codes linked to apps or informational platforms—or by facilitating disposal through automated identification systems like digital watermarks. It can also support the design of lighter, more efficient packaging by reducing over-packaging, enabling easier disassembly of components, improving material separation for proper disposal or reuse, and fostering recycling, including through the use of artificial intelligence and predictive algorithms.

From a social perspective, well-designed Smart Packaging can increase accessibility to information for people with visual or cognitive impairments through the use of digitally enhanced labels, integrated voice messages, or augmented reality; ensure transparency regarding origin, ingredients, traceability, and environmental impact; promote awareness campaigns on socially and environmentally relevant issues; and educate consumers toward more informed choices, encouraging virtuous behavior even in the post-consumption phase.

Economically, Smart Packaging can help reduce operating costs through predictive monitoring and data-driven maintenance; support circular business models; and enhance brand reputation through the credible and verifiable use of green technologies.

Smart Packaging can meet sustainability goals when its advanced functionalities are designed to address real needs, reduce environmental impact, and promote responsible behavior. This is the case, for example, with the solutions developed by Faller for the pharmaceutical sector, which integrate connectivity and sensors to improve traceability, therapeutic adherence, and the personalization of information.

In addition to the integration of sensors, indicators, and data carriers, Smart Packaging is based on a set of complex yet widely adopted technologies known as Core Technologies: Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, artificial intelligence and machine learning, cloud computing, 5G, big data, and immersive environments. Their combination makes it possible not only to collect data, but also to interpret it, return it, and leverage its value throughout the entire product life cycle.

Packaging is thus enhanced with tracking and tracing functionalities, including GPS-based systems; tamper-evidence and anti-counterfeiting features through unique and verifiable codes; personalized user interfaces that provide usage instructions, educational content, or immersive experiences (AR/VR); and real-time or asynchronous consumer interaction and profiling, following reward or engagement logic. In some cases, these technologies can also facilitate reuse practices, enable new service models, or make information flows more transparent and distributed throughout the entire supply chain. Additionally, they can strengthen the narrative dimension of packaging, turning it into a cultural mediator capable of clearly and engagingly conveying the story, features, and impacts of the product. However, these very functionalities raise important questions: what happens to the data collected by packaging? How is it stored, processed, and shared? Who benefits from it, and who risks being excluded?

It is fair to ask whether these technologies are truly accessible to everyone, or whether they create new forms of inequality—between those who have the tools and skills to interact with them and those who are left behind. In an increasingly interconnected context, attention to inclusivity is not a minor detail, but a design responsibility: it means providing different levels of access, offering analog alternatives, and ensuring that innovation does not become a new source of exclusion.

Despite its promises, Smart Packaging is not without risks and critical issues, which must be acknowledged to avoid uncritical adoption or opportunistic use. Among the main challenges are recycling difficulties: components such as sensors, tags, or batteries can hinder material separation and increase environmental impact. Added to this is the risk of rapid obsolescence, as integrated electronics may make the packaging non-reusable or difficult to upgrade. Equally significant are issues of access and inclusion, especially for consumers less familiar with digital technologies, as well as privacy concerns when data tracking leads to opaque forms of control or profiling. There are also high costs, which make some smart solutions unsustainable for SMEs or low-margin products; and the risk of “technological greenwashing”, when the “smart” label is used opportunistically without delivering real environmental or social benefits. To ensure that the potential of Smart Packaging is not undermined by superficial claims or speculative logics, it is essential to define shared guidelines, promote ethical and interoperable standards, and develop new design skills that integrate technology, design, and responsibility.

It is therefore necessary to complement technical innovation with critical and systemic thinking, capable of questioning the effects, implications, and limitations of the proposed solutions.

Designing smart packaging also means knowing where and when to stop, when to simplify rather than add, and when to choose simplicity over unnecessary complexity.

Smart Packaging can represent an extraordinary opportunity to build a new relationship between products, people, organizations, society, and the environment. It can become a platform for collaboration and shared responsibility, capable of generating not only economic value but also social and environmental value. But for this to happen, it is not enough to make it more efficient or engaging—it must also be designed around values such as equity, transparency, and foresight. Moreover, the intelligence of packaging does not reside solely in its circuits or algorithms, but in its ability to raise awareness, encourage responsible behaviors, and guide change. This is where true innovation lies: in designing better—with greater care, deeper listening, and a stronger sense of limits. In a word: more ethics.

[ Disclaimer. This is a non-commercial article distributed solely for the purposes of information, criticism, or teaching. All trademarks mentioned belong to their respective owners; the rights related to product names, trade names, and product images are the property of their respective holders.