[01. Responsible

Packaging becomes responsible when it is a shared responsibility of everyone toward everyone else: in its design, production, and use. Responsible packaging delivers quality, combining environmental protection with respect for the needs of all users.

Exhibitions in a Box: from the museum to packaging between staging and responsibility

“Packaging is theatre,” Steve Jobs once said. Like Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise, every package is an exhibition device that sets up a scene and orients its interpretation. The interpretation of a content unfolds between the construction of mechanisms of seduction and forms of manipulation. Staging requires design responsibility.

Opening a package means crossing a threshold, a passage designed to prepare perception and only later the use of the content. Before the product is fully visible, the recipient enters a space that directs the gaze and prepares interpretation. As in theatre—albeit on a reduced scale—they encounter a scene constructed through materials, surfaces, volumes, and informational rhythm.

La Boîte-en-valise di Marcel Duchamp exemplifies this dynamic with remarkable clarity. Created in several editions between the late 1930s and the early 1940s, it appears as a series of suitcases and boxes that gather reproductions of his works, presenting themselves as “portable exhibitions,” micro-installations in which each element is arranged according to an intentional sequence. They are pocket-sized architectures designed to guide reading and interpretation of the content, rather than preserve an archive.

Each reproduction is selected, positioned, and ordered according to exhibition criteria. The suitcase thus becomes a small itinerant theatre, a container that does not merely preserve but stages. Opening it means entering a curatorial path.

This principle, based on selecting, arranging, and guiding the experience, is especially helpful for interpreting contemporary packaging as an exhibition space. Visibility is never accidental, but results from design decisions that define what appears and what remains implicit. Considering packaging as a theatrical scene means recognising that forms, materials, surface treatments, and graphic elements contribute to constructing the experience. Thinking of packaging as an “exhibition in a box” implies that every visibility choice has consequences: what is shown builds trust; what remains implicit affects credibility.

The staging of packaging is built through three operative components that determine how the recipient interprets the container and, consequently, the product.

The first component, syntax, concerns the configuration of the elements of the package, both structural and graphic. It indicates what is immediately visible, what emerges later, and what stays in the background. From a graphic perspective, the product name is clearly legible, the main information is close and connected, and nothing disrupts reading. From a structural perspective, it is clear where to open the package, how to access the content, where to tear, what to lift, where to apply pressure. Effective syntax guides the gaze along a predictable path; if syntax is weak, everything seems to have the same weight, mixing priorities and generating confusion.

The second component, expressive style, is the communicative mode through which the package presents itself. It is not about decoration, but about the tone of voice with which the packaging addresses the recipient. It may be more technical, more institutional, more childlike, or more ironic. Style helps immediately understand what type of experience the object offers and maintains coherence with the brand and product identity.

Finally, the third component, scenic personality, is the answer to the design question ‘How does this package want to be perceived?’. Every packaging relies on a design metaphor, a ‘as if it were’, that orients interpretation. It may present itself as a technical accessory designed to offer precision, as a manual designed to provide clear instructions, or as a precious object that communicates care and value. These metaphors define the project’s intention and make interpretation more immediate. A defined scenic personality makes the scene readable and stable; an incoherent personality makes perception more complex, both of the container and its content. The design metaphor is not a conceptual ornament but an operative criterion that guides the entire user experience.

Many twentieth-century artistic experiences show how a container can transform into a scene capable of orienting the experience: from Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise to Joseph Cornell’s shadow boxes, up to Yoko Ono’s Everson Museum Catalog Box, every ‘exhibition in a box’ organises experience and constructs meaning.

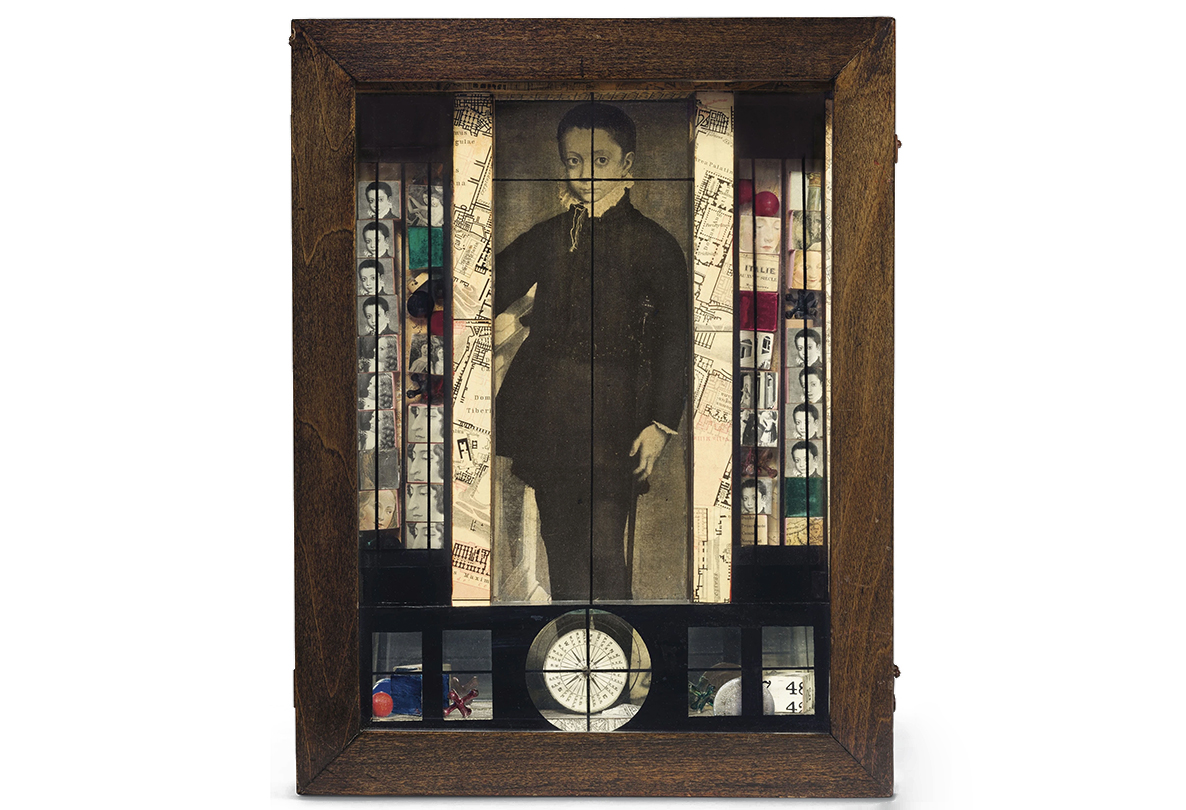

In the 1930s, Joseph Cornell iintroduced one of the most influential interpretations of this logic. His shadow boxes are vitrines designed to define a precise viewpoint. Inside them, Cornell arranges photographic reproductions, toys, decorative fragments, and small objects found in New York flea markets. The box does not preserve but constructs a montage: it selects what coexists in space and transforms it into a coherent micro-installation. The rigid frame and sometimes the painted grid confer order; unexpected juxtapositions introduce a controlled imaginative dimension.

The Medici Slot Machine series enhances this logic by transforming the box into an interactive device. Inspired by vending machines and penny arcades of the 1930s, these boxes contain small blocks of images, maps, and manipulable reproductions. The scene is not fixed: it is activated through the gesture, and the experience unfolds over time.

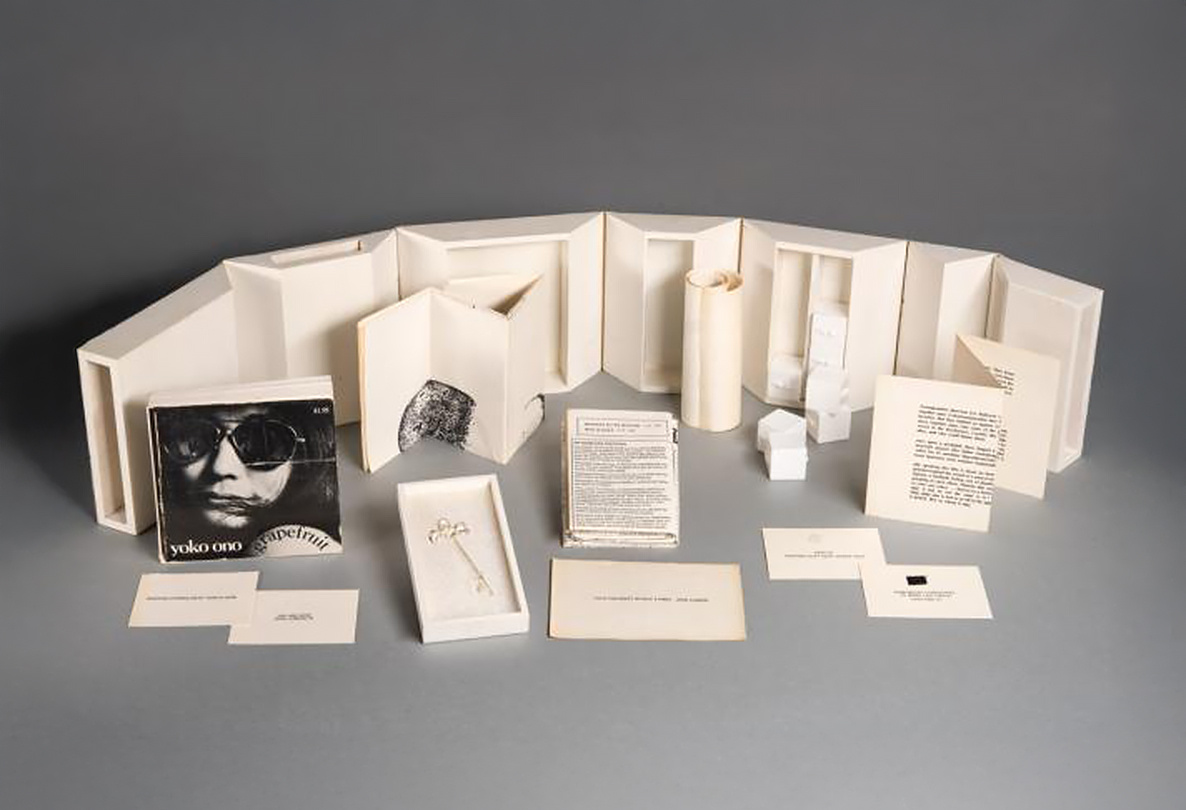

In the 1960s, Fluxusmovement introduced another interpretation of the container as scene. The Fluxus Boxes hold heterogeneous objects and brief instructions that acquire meaning only upon opening. Fluxus encompasses collective formats like the Fluxkits, assembled by George Maciunas, and authorial boxes such as Everson Museum Catalog Box di Yoko Ono, conceived as autonomous experiential devices.

During the same period, Joseph Beuys used the box as a conceptual statement. His essential containers—often in wood or metal—hold industrial or organic materials. Here the box does not construct a world but a boundary. To enclose means to isolate a set, separate it from the context, and assign it a value. The structure itself establishes the status of the content: the container becomes a limit that organises perception, not merely a protective space.

In the early 2000s, Justin Gignac developed the New York City Garbage project, based on small transparent containers holding fragments of urban waste.The content remains ordinary, but the scene constructed by the vitrine transforms it. Transparency, proportion, and formal cleanliness make readable what would normally go unnoticed. The distance between object and surfaces, and the fixity of the frame, create a controlled observation condition that reshapes the perception of the content.

These mechanisms, born within the artistic field, become even more evident when transferred to packaging, where the scene must function in a repeatable and consistent manner, making the product readable, orienting the gesture, and building a reliable relationship between content and recipient.

Moving from art’s micro-scenes to packaging means observing how the same principles change scale when entering the production cycle. In artistic works the box is a unique piece, designed for a singular experience. In packaging, instead, it must work in series, maintaining coherence and immediate comprehension. But the underlying logic remains the same: defining what enters the scene and how it should be experienced.

The scene of packaging is not neutral: it frames the product, orients interpretation, and organises reading. Even minimalism is a design choice that constructs rhythm and priorities.

In the transition from the artistic to the commercial field, the principle remains unchanged: the container is a system of decisions. Forms, surfaces, transparencies, and graphic elements define the perceptual field in which orientation and trust are determined. Packaging is not spectacle but a communication infrastructure that must be clear, repeatable, and coherent with the context of use.

When the container enters the market, the scene becomes a competitive tool. Packaging is a micro-architecture that concentrates identity and information in a reduced space. Its effectiveness depends on how elements are selected and organised: what appears in the foreground guides recognition; what remains in the background completes the picture; what is implicit still contributes to the overall meaning.

Thinking of packaging as a scene entails precise direction. Every element must respond to a design intention: what must appear first, what must accompany, and what must remain as background information. This direction concerns not only graphics and text but also structure: forms, volumes, thicknesses, and opening points influence the reading sequence as much as visual layout.

Opening is a key moment. It is not a simple mechanical gesture but a dramaturgical act that introduces the product and prepares its use. A package that opens intuitively makes the transition between the external and internal scene immediate; one that forces unexpected gestures breaks continuity and generates mistrust.

Another design responsibility concerns the management of sequences. Effective packaging does not accumulate information but constructs passages: what is immediate, what can be explored, what is discovered later. Packages that sum elements without hierarchy generate noise; those that distribute content according to a narrative order reduce cognitive load and improve experience. Defining hierarchies is an essential component of the scene: the recipient must immediately recognise what is important, while the rest accompanies without interfering.

Considering packaging in terms of staging means recognising that every visibility decision is an ethical decision: it is a system that orients gesture, choice, and trust. Showing and omitting are not neutral operations: they define what the recipient will know immediately, what they will discover later, and what they may not see at all. In this balance lies the brand’s credibility.

Responsible staging guides attention without distorting it: it offers what is needed for informed decisions, not what complicates them. Selection concerns not only texts and images but also materials and finishes: everything contributes to constructing a more or less clear narrative. Narrative transparency emerges from this intention: making the content, its use, and its implications immediately understandable.

In this sense, readability is not only a communication value but an ethical criterion. Organising the scene without visual noise means respecting the time, skills, and expectations of those who use the package. Clarity does not reduce product complexity; it makes it accessible.

The ethics of staging requires cultural accuracy: every visual, symbolic, or linguistic reference must avoid stereotypes and superficial appropriations. A responsible scene recognises the plurality of recipients and adopts an inclusive language that neither excludes nor distorts. It is another form of transparency: allowing different interpretations without imposing one.

Finally, scenic honesty concerns the coherence between what the package anticipates and what the product actually offers. The ability to attract is not a problem; it becomes one when seduction conceals essential information or leads to misleading readings. If the graphic or structural arrangement excessively amplifies the image of the product, the scene becomes deceptive.

The responsibility of the scene is measured by its ability to build trust. A package is ethical when it allows the recipient to quickly understand how the product is made, how it is used, which materials it contains, and which design decisions influence its impact. Simplicity is not reduction but clarity: a criterion that ensures continuity between design, use, and real value.

The lesson of artistic micro-scenes is clear: the container is never neutral. Duchamp, with his suitcase-installation, showed that a reduced space can organise meanings, orient the gaze, and define a reading path. Transferred to contemporary packaging, this principle reveals that every package is a pocket theatre preparing the encounter between content and recipient.

Viewing packaging as a form of staging implies recognising that the project constructs an interpretive experience. It is not simply a matter of containing an object but of defining expectations, gestures, and understandings. The designer thus assumes a curatorial role: they must structure an environment that is readable, coherent, and responsible.

When the scene is rigorously designed, it offers transparent interaction: it shows what must be visible, provides essential information, and creates continuity between promise and real use. Viewing packaging as a pocket theatre means recognising that competitiveness does not arise from overstimulation but from transparency. The value of the package depends on its ability to orient, inform, and generate trust: the scene is not a decorative detail but the visible form of design responsibility.